As a writer, I’m always asking myself whether I should be reading or writing–there’s only so many hours in the day, so many years left before I’m senile, so much electricity left before a magnetic sun storm wipes out civilization as we know it. Do I really have time to read? Shouldn’t I use every spare moment I have to write? To produce something? Reading something, especially a book, seems so indulgent in this age, so mentally fattening. I don’t have time to sit by the fireplace (which is never lit anyway) and curl up with a book. When I do take a break after a busy day, I either look at Facebook or turn on the flatscreen to watch movies or my favorite HBO series because I can multitask (knit, fold laundry, eat) while I absent mindedly watch.

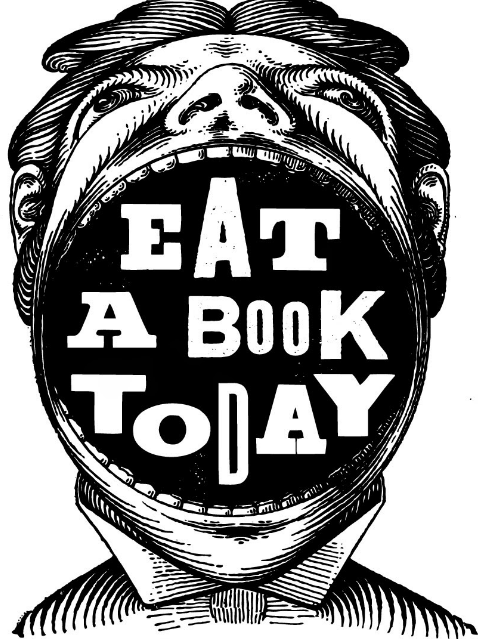

But every once in a while I have the urge to stop consuming junk food, and fast. I turn off the computer and TV, and I pick up a book. And another book. And another book. Interestingly, when I take the time to stop writing, I have the urge to wolf down as many books as possible, in other words–binge reading. Then, to continue in my lovely eating metaphor–I have the urge to write about what I binge read–in other words–vomit out my thoughts in the hopes that a few nuggets of wisdom have remained in my brain that I can share with you.

Over the past few weeks, I read or re-read In Other Words and Unaccustomed Earth by Jhumpa Lahiri, The Seamstress by Sara Tuval Bernstein, Half Broke Horses by Jeannette Walls, Unforgettable by Scott Simon, The Boys in the Boat by Daniel James Brown, and three books by Alexandra Fuller: Don’t Lets Go the the Dogs Tonight, Cocktail Hour Under the Tree of Forgetfulness, and Leaving Before the Rains Come. As you may have noticed, these are narrative non-fiction books–“true stories”– except for Lahiri’s Unaccustomed Earth (a collection of short stories.) But even Lahiri’s fiction is firmly rooted in her life experience as a daughter of Indian immigrants. One reason I choose to read these books is for practical purposes–I need to read good non-fiction writing in order to write good non-fiction. But the other reason I’m drawn to these stories is their texture. The vitality, layers of meaning which seem to have grown in the rich soil of true life. For some inexplicable reason, a sentence written by someone who has truly experienced a tragedy, a trauma, a story rings much clearer–feels more visceral–than one written by someone who pulls it out of a hat.

I’ve picked out a few lines from Leaving Before the Rains Come because they are relevant to my own writing. Like me, Fuller is of the immigrant culture (a white girl who grew up in Africa and moved to Wyoming). In this book, Fuller explores her marriage and divorce. She explains her attraction to Charlie, a white American from an old Philadelphia family.

“I suppose in some instinctive way, I believed that Charlie would be the route back to something more solid and enduring. After all, inasmuch as settlers of anywhere could be, he was of this nation; too many generations to count back how long his people had been here. Our children would be able to stand unabashedly unshod upon this soil, they would sense their ancestors, they would feel a belonging.”

Although I write from the perspective of a Nisei, a Japanese-American who lives in predominantly white Colorado, I think that anyone who feels lonely, who longs to belong to a community, can relate to Fuller’s words. Every newcomer tries to connect to others by finding that rock, the solid person who seems to be firmly rooted. But Fuller also writes about the feeling of alienation from, not only other people, but from those who only remain in our heads.

“There is no loneliness quite like the loneliness that comes from living without ancestors, without the constant, lively accompaniment of the dead.”

Perhaps Americans, whose dead are safely locked away in antiseptic morgues and cemeteries, might have a hard time understanding this type of loneliness. Bernstein’s WWII memoir, The Seamstress, based on her childhood in Romania and the grim Ravensbruck concentration camp is littered with lively, colorful characters–some wise, some foolish, some brave– all dead now. Bernstein’s story was dictated by all the ghosts in her mind. In Japanese culture, for example, one never says goodbye to the dead. There’s the tsuya (wake) first, then a funeral, then a kotsuage at the cremation, then ,shonanoka seven days after death, and the shijūkunichi 49 days after death, and another memorial 100 days after death. At the annual Obon festival everyone celebrates the dead by visiting graves, reminiscing, dancing and telling ghost stories. Then as if this wasn’t enough, at home, in between these death gatherings, I’ve seen Japanese offer food to the small urn of ashes before every meal, and share the news of the day –“Look, isn’t this a lovely handbag I got today”– as if the dead were sitting across the living.

In my current writing project, translation (Japanese to English) is an additional challenge to coming up with my own writing. I translated my deceased father’s Japanese letters and used them as an anchor to write my own thoughts. Jumpa Lahiri in In Other Words, described the process of translation beautifully:

“I think that translating is the most profound, most intimate way of reading. A translation is a wonderful, dynamic encounter between two languages, two texts, two writers. It entails a doubling, a renewal….It was a way of getting close to different languages, of feeling connected to writers very distant from me in space and time.”

Translation is to writing as crawling is to hiking. It’s a lot slower and messy but one is still working towards the same objective: to connect to a different place and time. To get from one place to another across the landscape of life through words. Words written in another language. One may stumble over the rocks, the individual words, and fall occasionally but those accidents are what add joy and interest to the journey, and satisfaction when reaching the end.

Finally, one more twist to the metaphor I started with–eating. Eating books is not just about digesting the contents, getting through all the pages. I like to think that reading is to writing as tasting is to cooking.Of course, it is possible to cook without tasting, but then how can one develop the nuances, the textures, the complexity of a unforgettable meal? I hope that as the words of these books I read slip through my retina, I took notice of them. I let them sink into my mind. If I occasionally stop to reflect and write about certain passages, maybe their wonderful qualities will remain in my brain, ready–I hope–to be sprinkled into my own writing like subtle seasoning. I know that the question isn’t one of whether I should be reading or writing. One cannot be separated from the other, just as eating cannot be separated from speaking. Without food, one’s voice will soon fade. Reading is life.