Thanks for Your Reviews

Tei has been generating positive reviews in Amazon where there are 17 five-star reviews as of this date, and in Goodreads where Tei has earned an average 4.81 star rating with 26 ratings and 18 reviews. Thank you for your comments and reviews.

Thank you

Thanks to almost six hundred readers who signed up for the Goodreads book giveaway. The fifteen free books have been mailed out to the lucky winners all over the U.S. We look forward to comments from these readers as well as anyone interested in Tei’s survival story.

Please add your comments to the reviews already posted on the Goodreads.com page for Tei, a Memoir of the End of War and Beginning of Peace.

We are especially interested in hearing from those of you who have a direct personal connection with the events of Tei’s memoir. For some, this book has opened the door to painful memories. Memories which will illuminate a part of history many have not heard of.

Thank you for sharing your personal and complex emotions from that difficult time in our world history.

Sign Up for the Book Giveaway Before Friday August 29, 2014!

Go to the Goodreads website (book review site) and the page for Tei, a Memoir of the End of War and Beginning of Peace. Scroll down to find the button marked “Enter to Win” to sign up for a chance to win one of fifteen free books which will be given away the end of this week. While you are there, check out the reviews written by readers like you. This is a website which only focuses on BOOKS and it’s a fascinating place to find out what people are saying about books and to add your own two-cents.

Chapter Twelve

Diamond Dust

November arrived, and there were nights where a cold northwest wind blew so hard it rattled the windows, and kept me half-awake until morning. Once there was enough light, we looked for branches the wind had torn off the trees—sometimes I found enough for an arm load. Later in the day, when the sun had warmed the ground, we went down in the hill to town. On the west side of the dirt road, apple stands started appearing.

These apple stands soon formed two red parallel lines all the way down to the train station entrance. From the mountains in every direction, hand-carts full of dried grass began to creep along the roads, dropping their loads into small haystacks here and there. Ox carts would then collect these haystacks into huge loads, and one by one, they lumbered between the lines of apple stands into the town center.

I guessed the dried grass was for the town’s ondoru Korean floor heaters. In the morning, smoke climbed from the many ondoru and make thin white layers in the air. Our lonely house at the top of the hill, where the men were gone, also let sad, bitter smoke out from the ondoru twice a day. Winter was coming.

Just after the middle of November, early in the morning, someone came knocking at our door. This felt ominous so early in the day. As we all got up, Dancho Narita brought in a Korean boy who was breathing hard and sweating. He had brought messages from the town of Anton, just north of us on the border with China. Mrs. Tomimoto, Mrs. Yamada, and Mrs. Sueyoshi got letters and money and they beamed with happiness as they read letters from their husbands. The messenger boy said, “Hurry. Hurry,” while the three women wrote letters for him to take back to Anton. The boy looked worried, and kept looking out the door.

As soon as the letters were done, he grabbed them, and ran down the hill as if flying on the wind. After two or three such letter exchanges with Anton, four women with their children, ten people altogether, decided to leave us and go north to Anton to join their men there. A fine powder snow fell that day, and we saw them off. We called out, “Sayonara. Take care of yourselves,” as the women and children disappeared into the snow.

Our group was now reduced to twenty-nine people. Once December came, the authorities decided that we would be rationed two Japanese go (about a cup and a half) of rice a day for each person. I was so happy at first. This rice would help us survive the winter. But then our dan decided to re-distribute this rice amongst us. For children under five, the ration was cut to half that of the others, in other words, just one go a day. The extra rice was saved to distribute to the women who worked for pay. With this new distribution system, the ones who suffered the most were the women with young children and babies: me – I lost two go, Mrs. Honda lost two go, Mrs. Sakiyama also lost two go, and Mrs. Daichi lost one go. We mothers with little children were the most desperate of the refugees. In this life, we endured and suffered the most. I wondered if this was my fate, determined from my date of birth. What is going to happen to my three, pale-faced sickly children?

Once the snow started, tiny ice crystals blew incessantly around in air. I’d seen this snow often in Manchuria where the temperature often dropped below freezing. The air was dry and the skies were clear. The snow particles stayed suspended and sparkled in the sun. It was breathtakingly beautiful. I had heard my husband describe such snow as “saihyo.” But he also used another name in English, “diamond dust.” That English name was so wonderful, I never forgot it. Diamond dust. There were times the snow really looked like that.

In my hometown Nagano, where winters were cold, there is a phrase we used—”ice drying”. This refers to when the laundry is hung out to dry in the winter. It quickly froze stiff, but before you knew it, the clothes would be dry. In order to dry Sakiko’s diapers, I hung them facing the sun. The wind pierced the red cracks in my hand like needles as I hung the wet cloths every day.

Now it was so cold the snow did not melt. When I walked on the icy road, my head would ache, throbbing with each step on the hard ground. Somehow my hunger made the frozen ground feel even harder.

Our toilet froze. The daily waste, instead of flowing down as usual into the pit, now froze in place, growing taller and taller. We shoved the waste down after we used the toilet each time, but finally, this grotesque ‘tower’ of feces and urine would not let loose, even if we hit it with all our strength. So we made a special toilet. We placed a large wooden bucket upside down and left boards on top beside the crude toilet opening to step on. That way, we could move the toilet away from the icy mountains of waste.

But every morning, we took turns cleaning this nasty, frozen mess up. It was the most unpleasant chore we all shared. And those of us with small children bore the brunt of everyone’s frustrations. Mrs. Nagasu, with her one five-year-old daughter, and enough money to pay for heating fuel, complained the most. Small children inevitably made the biggest messes so she haughtily said, “We need to have those with small children do more of the toilet clean-up.”

Chapter Eleven

Making Ourselves Invisible

The locals called us Nihonjin, (Japanese) and none of us were upset because that was obvious. But if any of us called them Chosenjin, (Koreans) they got very angry. (It was the pent-up rage from many years of Japanese military rule.) In order not to provoke them, we decided to call them, “the people of here.” But if we weren’t careful, the words still slipped out of our mouths—Chosenjin.

The north wind that started blowing during the night kept gusting with the arrival of morning. We huddled in the corners of the rooms with rounded backs when the west-facing window shattered with a loud crash. We looked at each other. Another window broke.

A young Korean yelled something. When we peeped outside, we saw five or six kids, maybe fourteen or fifteen-year olds. They held rocks in both hands, and threw them at our windows. I rushed over to get Sakiko—any of these windows might be next.

Dancho Narita got up unsteadily and closed the northern window shutters quietly. Then all of us women and children hid in the darkened room. My children said nothing as they held onto me, letting their noses drip. If we could reach the Hoantai, the Korean police, maybe they would help us. But who was going to go from our house, down the hill to let them know? No one had the courage. If we went outside, were we going to be beaten? Maybe some thugs would kill us or worse…we were terrified. Even Dancho Narita trembled.

Through the cracks in the window shutter, we saw a white neck scarf of one of the boys. I tried to comfort Dancho Narita by saying, “Dancho Narita, maybe we could fix the broken window with a piece of paper.”

He just said, “Those stupid kids.”

After a while, we heard footsteps run over to our kitchen, Bang. Crash. There was the sound of metal banging into something. A boy said in Korean, “Hey, there’s a hango.” After some rustling, there was no noise. In a rush, we ran over to the kitchen.

Five of the hango that we had kept were taken. There was only one left. “If we don’t have our hango, how are we going to cook?” Tears streamed down Mrs. Daichi’s thin face. “And I had stuffed mine full of potatoes…for our dinner.”

Seiko-chan pulled Mrs. Daichi’s sleeve, “It’s no use crying, Mama.” And she went back into our room.

There were days when shifty-eyed Korean men hung around near the house. And days when boys drew nasty graffiti on our house. Some men came, saying they had messages from our men in Heijo. They banged on our door, claimed they had business with our men, and looked at us with suspicious eyes. The Koreans who were sympathetic no longer came near. If we passed each other on the street, they slipped the children an apple or a piece of candy. Most of those people were elderly. The young Koreans tried to not look at us as they passed by.

We didn’t know what would happen if we ran across the Koreans who really hated us. They could do anything and we wouldn’t be able to defend ourselves. We were terrified whenever we had to go outside, and shrank into ourselves in an effort to make ourselves invisible. The children learned this, too, and when they saw any townspeople, they covered their frightened faces and hid behind us.

Chapter Ten

The Hill of Tears

The autumn sun rose high as we stayed on the hill, silently crouched, even after we could no longer see the vapors left behind the steam engine of the train. The crowd at the train station disappeared, and everything had settled into a frightening lull. We wept silently as we faced the distant mountains. One by one, the women whose husbands had left, went alone to a rock or a grassy spot to grieve in private.

“Mrs. Fujiwara.” When I turned around, I found Dancho Oe standing. As the head of our group, he had accompanied the men to the train platform.

“I was asked by your husband to return this to you.” In his hand, Dancho Oe was holding a blanket and woolen underpants.

“Why?” I said as my eyes filled with tears.

“He was worried about you. He thought you would have a hard time,” he said. “He also told me to give you this money.” There was three hundred yen in his hand.

“What an idiot!” I scolded my husband silently. Going to the gulag in Siberia, why did he give me back his most precious things? It’s like some sort of love suicide. Maybe he thought if he left these things for the children, I’d be satisfied. But now every day, every night when I saw this blanket, I would be reminded of him. I was so angry at him for leaving me, I forgot to thank Dancho Oe—he stood there, waiting.

Finally, he said, “Mrs. Fujiwara, you might not know about it…a while ago, at the marketplace on the way back from a meeting, I lent your husband forty yen…”

“What…what about forty yen?” I mumbled. A look of annoyance flitted across his face.

“I lent him forty yen,” he said.

“I don’t give a damn about forty yen,” I thought. I couldn’t stand to look at his face as he tried to collect on a loan—to bring this nasty business up when my heart was breaking. I paid him the forty yen. The thought suddenly surged through me, “From today…I’ve got to be strong.”

Near our shinto shrine house on the hill, the other women stood in a circle and looked towards me. They were the women who had always been alone, their husbands missing since we left Manchuria. From the hill, they looked down at the seven women who just lost their husbands, and whispered amongst themselves. I looked at them, then they averted their eyes, as if they had been saying something bad.

One of them, Mrs. Nagoshi, said to me, “Okusan (Ma’am), it’s going to be hard for you now.” She had one nursing baby and was the youngest wife in our group. Was she trying to be polite, or comfort me, or provoke me? I didn’t know. I’ve got to be strong. I looked at the faces of my children.

Masahiro, still stunned, came near me, and from time to time looked up at me, trying to understand what had happened. Masahiko-chan was angry—the pain of separating from his father overwhelmed him. I worried about Sakiko and went back to my room, the boys following close behind. It was unusual to find no one else in the room. She was asleep.

I picked her up and said, “Sakiko. Daddy is gone. Sakiko, he’s gone.” I rubbed up against her sleeping face and sobbed. I felt so miserable, but my three children understood me best. Masahiro, with his eyes full of tears, stared at me. For three days, I was in a daze. A voice, somewhere inside me said, “You’ve got to get a hold of yourself,” but I could do nothing. Wherever I was, I was in tears, and consumed by heartache.

The four men left behind went back and forth to the main office of the Japanese Association. They talked importantly amongst themselves. Mr. Narita, who until now had been ignored, became one of the inner circle of men. When they announced that the age limit of forty, Mr. Nagasu was exuberant, and for two or three days, he worked energetically, and annoyed me by saying, “Okusan, it’s no use crying. You must get to work.” He bossed the women around and stuck his nose in the cooking pot, commenting on the food. Then on the night of the third day, he suddenly became quiet and his head drooped. I thought he was sick and asked Mrs. Daichi about him.

She said with a worried look, “It turns out that all of the men are doomed. Unless a man is really sick, everyone of them—up to age forty-five is going to be sent away.”

“Is that true?”

“I think so. I don’t know what to do.” Her husband, Mr. Daichi would be sent away and their daughter, Seiko-chan, would be devastated. I don’t know where that rumor came from but the remaining four men suddenly lost their spirit and began packing up their things. Four days after my husband left, I finally came back to my senses. There was no time to grieve, I knew I had to think about the future.

The morning of the fifth day after our seven men were taken away, the same station master knocked on our door, just as he had done before, to bring bad news. He announced that the remaining four men would be shipped away. The next morning at 8 a.m. the remaining men up to the age of forty-five gathered together at the school. Former Dancho Oe; Mr. Nagasu, no longer proud; and poor Mr. Daichi, held his daughter, Seiko-chan’s hand. Mr. Narita, a weak man who was often feverish, couldn’t move with the other men. Thankfully, because of his illness, the authorities let him stay.

I went through a repetition of the same horrible events of five days earlier, but this time I was the witness. Dancho Oe handed over the dancho responsibilities to Mr. Narita, then he talked in private with his older sister, Old Woman Oe. After three months as our leader, Dancho Oe was feared more than respected by us. Now he bowed his head, like a beggar monk, before us women and spoke.

“Thank you all for everything. I ask you to take care of my sister,” he said humbly.

I bowed my head to the man who at one time, forced my husband to apologize for some silly offense, with both hands on the floor. I hated him before for that, but now I felt nothing. Seiko-chan cried out in anguish, “Papa. Papa,” as she clung to her father. The fourteen-year old girl couldn’t be stopped by her mother and she held onto Mr. Daichi, crossing the hill with him. All of us were in tears watching them.

“Take care of yourself. Don’t do anything rash,” Mr. Nagasu said to his wife and five-year old daughter, Hisako, as he kept turning his shoulders around, over and over, to see them as he walked down to the station. This once proud man was crying, and I felt guilty for my earlier feelings about him.

Dancho Narita, with his fever, struggled to keep his reddened face up and stand on the hill. We watched the train go past the hill again. This time, there were much fewer men on the train.

From our vantage point on the hill we heard Mr. Nagasu calling his daughter. His voice was cut by the wind, “Hisako…oh, Hisako…oh.” His dark face strained to see his only daughter, and that voice…by the time the vapors floating horizontally from the steam engine faded, the train was on the other side of the mountain and his cries were gone.

I took tally of my group. Now we had:

Males: only Dancho Narita.

Females (Married women): sixteen.

Young single women: (Mrs. Kurashige’s young sister, Kuniko), one.

Unmarried older woman: (Mr. Oe’s older sister), one.

Children: twenty.

Total: thirty-nine people.

Under the leadership of our sick Dancho Narita, our small group of thirty-nine women and children would have to go forward beginning tonight, together with new tears.

Chapter Nine

Where is My Husband Going?

In the yard there was a single small maple tree. This tree was in the shape of a sideways letter V and from the top, three branches sprouted from the same place. It was October when these maple leaves turned. We had to wear socks to bed, otherwise our cold feet woke us in the middle of the night, but the afternoons were still warm.

As I hung diapers to dry on the tree, I heard something. When I looked up, an airplane, one with markings that I had never seen before, flew north. A Korean man asked quietly, “Is Mr. Daichi here?”

I turned around to see the train station master standing there, half-smiling. Most of us didn’t know what was happening in the war but Mr. Daichi found a source. On his daily walks, he became friends with this Korean station master. I wasn’t surprised. Mr. Daichi was good with people—making anyone feel at ease. Every evening, he snuck down the hill and listened to the station master’s radio and heard all sorts of news. This is where we heard: the hikiage, the repatriation would begin in November.

I showed the station master up the hill to Mr. Daichi and, felt anxious—is there something new going on? By coincidence, I heard the same news about the November hikiage through my husband’s distant relatives, an elderly couple who lived nearby, called Old Man Gomi and his wife. He used to be an elementary school teacher in northern Korea. They lived in a small place and started quietly bringing us things (mostly old magazines, paper and other useful things).

Around October 20th, Old Man Gomi came around and told us he heard through another Japanese group that the hikiage would be in November. “If it’s possible, I wanted to ask if we could be included, to go home,” he said. My husband tried to find out where that rumor came from but Old Man Gomi didn’t know. Maybe it started with the station master’s information? Old Man Gomi laughed and went back down the hill.

Around October 25th, there was more activity in the town and more trains started coming and going. Our hearts beat with excitement—maybe we could go home to Japan! When the men returned that night, sounds of laughter filled with hope floated through every room. The next day, we started preparing candy and other portable food. But, other than trains passing through the station, three or more times a day, nothing happened.

A gentle knock on the front door woke us from a deep sleep on the morning of October 28th. It was Mr. Daichi’s friend, the station master again, but this time he asked for Dancho Oe and my husband to come outside together with Mr. Daichi. I felt uneasy. In every room, everyone woke up and we all quietly waited for the three men to return.

When they came back, I saw their faces were ashen, like those of the dead. I wondered, “What happened?” but our three men only said, “Hurry. Make breakfast,” and went into the small room to discuss something in private. When my husband came out to get a piece of paper, I asked him, “What’s going on?”

“I’ll make an announcement soon—just get things ready,” he said and rushed back to Dancho Oe and Mr. Daichi.

“Get ready for what?” I called out, but he didn’t answer me.

When I went outside, an early-morning fog completely covered the town. It was eerie to hear all sorts of sounds—children crying, things being moved—through the thick grey mist. Then from the school below us, I heard the shouting of men. All I could do was pace back and forth. “Get ready? How?” I thought, but I did as he asked and repacked all of our things.

Sounds of a horse climbing our hill were followed by the appearance of a man from the Hoantai Korean Police. He asked for our dancho to come right away. I couldn’t see where Dancho Oe and my husband went. Worried, I went out to wait. Out of the thick fog, my husband came back holding one of our ‘safes’, the tin can with emergency money. He hurriedly pulled out the money that was in the can.

“All Japanese men between the ages of eighteen and forty are to go to Heijo by train,” he said. “I’ve got some money for myself. I’m giving the rest to you.”

“What are you going to do at Heijo?” I asked.

“I don’t know. We might be sent to Siberia,” he said.

“Siberia?” I didn’t know what to say. The world was ending. Clutching the money wrapped in paper my husband gave me, I sank to the ground.

“Please hurry. Get my things ready. I don’t need money. Just the essentials,” he said nervously.

He had to get back to his duties for the group, taking care of the bookkeeping, and giving final instructions to those staying behind. Dancho Oe came back. “Within thirty minutes, all men between eighteen and forty years of age are to report to the front of the school below us,” he said. “Get ready right away.” A black cloud descended on everyone—except for Mrs. Nagasu whose face lit up when they announced “men up to the age of forty.” Her husband was forty-three. I hated the smirk on her face.

After they had their meeting, my husband came back. “This might be it. I may be leaving you for good,” he said as he put on the black suit I had repaired. We sat down to eat but couldn’t swallow the food. I stuffed the leftovers into a bento box for him. Looking through the clothes I packed in his rucksack, he said, “I don’t need this…or this,” and pulled out the winter clothes. I knew he was thinking of us. The Hoantai police came up to get our men.

“Hurry,” they said while avoiding our eyes.

When I tried to get him to take the blanket, my husband fought back fiercely. “I’ll manage,” he said. I pleaded with him, crying. Finally, I got him to take five hundred yen.

The final moment came and we looked at our baby, Sakiko still fast asleep on our blanket. Gently touching her cheek, he said, “She’s sleeping so well. She looks just like Masahiro when he was a baby.” Then he turned around and gazed at our eldest son who was standing beside me. Masahiro was doing his best to be brave. “This time, Daddy might not come back. Listen to Mommy, all right? All, right?” my husband said. Masahiro nodded and put his hand on my shoulder.

Masahiko was on my lap, his face nestled against my breast. He was only a two-year-old, still in need of mothering. At this tender age, he had been forced to deal with the arrival of his baby sister, and the war. Masahiko was so thin, his eyes seemed even bigger. He was my husband’s favorite and while I was busy with the other children, he took care of our middle child. One of their favorite activities was their walk to the bathroom every night. “Masahiko-chan, I want you to listen to Mommy, all right?” my husband said, but our son wouldn’t let go of my blouse. Instead, he stared at his father with huge terrible eyes.

My husband then turned to me. “Go home to Japan. Take care of the children.” There was so much to say but I couldn’t speak. As tears trickled down my face, I finally said, “Take care. All right?…Don’t get sick. All right?…Be sure to come back to us. All right?…”

Of our eleven men, those over forty years of age were: Mr. Narita, Mr. Daichi, Mr. Nagasu, and Dancho Oe. They would be allowed to stay with us. My husband and the six other men who were to be taken away from us gathered in front of our house. Facing us, one of them said, “Everyone…please be kind to each other. Take care of each other.”

After each man spoke, my husband came over one more time as I held Masahiko. He gently touched his son’s face. He used a favorite nickname and said, “Masa-chan, sayonara.” My little boy, who until now had been silent, suddenly started screaming. I wanted to scream even louder than him.

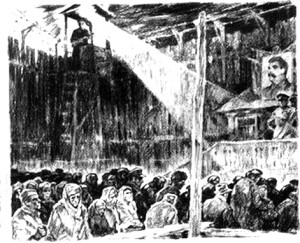

The fog began to lift. An open freight car was taking our men, and we stood on the hill to see them off. The train started moving slowly. Mr. Mizushima’s glasses glinted in the sun. I spotted my husband’s black suit right away. He waved his handkerchief and I waved a hand towel back. He waved his handkerchief in a circle. I waved my hand towel in a circle. We said good-bye. The train picked up speed and then passed behind a hill. October 28th was one of the saddest days of my life.

Chapter Eight

Corn Husks

That day my husband was working at a mountain three ri away (about seven miles). We women had finished washing clothes at the river at the bottom of the hill, and were on our way back when I saw a group of Korean men digging about. They were close to the spot where I buried some of our money. From the window at our sleeping area, our money was hidden beside a far rock, next to the third deciduous tree. But now a man in a hunting cap came up the hill, and as he dug here and there with a small shovel, he approached that tree.

Mrs. Daichi who was standing nearby said to me, “Okusan (Ma’am), he’s about to dig up your money!”

I shushed her to be quiet and held my breath. That man dug around the roots of a tree below my tree. He stepped closer to my ‘safe’. I couldn’t help myself and let out a small cry, “Ahh.” He stopped, rested his arm on his shovel, and looked up at us. At the same time, there was a loud noise from nearby, and a large rock came rolling down. Underneath that rock, a small can appeared. “Oh, no. Someone’s money’s been discovered,” we all knew.

The man with the hunting cap shifted his body and turned around to look. Maybe he thought that newly discovered place was more promising. In any case, he rushed over to that area, away from my ‘safe’. Several men focused their attention on that rock and began digging around its former resting place. They were obviously thieves but there was nothing we could do about it. We were just refugees, and could only helplessly watch.

Then a whistling sound drifted up from below. Somebody from the Hoantai, the local Korean police, came up the hill on a horse. Thank goodness. The thieves quickly disappeared. But Mrs. Sakiyama’s money was gone. In our group, she was probably the worst off or close to it. Her husband never returned, she was pregnant, and she had two young boys to care for. Of course, I hoped that wasn’t all of her money. I assumed she did what we all did. Divide the money into at least three parts before hiding it. Mrs. Sakiyama was usually morose but it was still terrible to see how she tried to hide her anguish. She refused to be comforted as she stood alone in her pain. I was relieved my money was still safe. I glanced at Mrs. Daichi and thought, “Wait a minute! How did she know my money was hidden there?”

I asked her, “Mrs. Daichi, how did you know my money was there?”

She smiled and said, “Oh, I’m not the only one. Everyone knows.”

The morning my husband and I hid our money, the fog was thick. We did it at mealtime when everyone was eating, I went to my room and was the lookout while my husband went to bury the money. I didn’t notice anyone outside of the house. “How did everyone know where our money was?” Now I was frightened.

I quickly ran to the bushes, dug up the spot, and checked our ‘safe.’ Although it stunk of dirt, none of the money was missing. It was wrapped in paper and tucked inside the bottom of the hango. I had carried it with my husband’s meal sitting on top and felt safe.

I sat staring at the hango, until my husband got home that night. Hiding the money in the house was dangerous. But hiding the money outside was dangerous, too. What could I do? Sewing a hundred yen bill in the seam of our clothes, in the collars, or inside the obi waist band, was too obvious—everyone knew about those hiding places. My husband and I continued to think about this problem everyday. He was so deep in thought that he no longer chatted with me.

One morning, during breakfast, he stopped eating. He was looking something outside through the window.

I said, “What are you looking at?”

There was only a corn husk someone had thrown away. When he was about to leave to work, he said to me in a low voice, “I figured out a way. I want you to collect as many corn husks as you can, and dry them.”

“What are you going to do?” I said.

“I’m going to make zori sandals tonight,” he said.

He must have some plan, I thought and did as he asked. I collected and dried corn husks all day. From that night, he started making zori sandals. He learned how to make them from Mr. Nagasu, a large, older man who came from a farming family.

Mr. Nagasu was curious. “Mr. Fujiwara, why use corn husks to make zori?” Traditionally, they were made of rice stalks.

“I did some research on this,” my husband said. “Corn husks contain oil and on top of that, they have very strong fibers. They make stronger zori than rice stalks. And did you know that even if they get wet, they won’t get soaked?” Saying such nonsense, my husband managed to deflect Mr. Nagasu’s suspicions. My husband’s first attempts were odd shaped zori, and Mr. and Mrs. Nagasu laughed at him because they looked so strange, but he didn’t seem to mind. It was late when he got to the third pair, working all alone. Each man took a turn as night watch. That night, my husband took the first night shift and worked on his zori sandals. He made four pairs with the corn husks. He hid hundred yen and ten yen notes, folded into tiny strips inside the corn husks—altogether about a thousand yen for emergencies.

I was impressed at his cleverness. “Not bad,” I said to myself.

As he instructed me, I wore those zori, got them dirty and kept them along with the children’s shoes, next to our rucksack.

And there was also my husband’s precious Longines watch. We hid that, too. This was another good idea. I carved a hole in a large bar of laundry soap, then wrapped the watch in paraffin wax and placed it inside the hole. From another bar of soap, I carved out a chunk of soap to seal the hole. After carefully filling in the cracks with soap flakes, I warmed the soap bar. As far as anyone could tell, we had an ordinary bar of laundry soap—with a watch inside! I even dipped it in water and used it a few times to show everyone it was just soap. The corners were all rounded and smooth and I kept it inside a can. In these clever ways, we kept our valuables safe.

After we put these ‘safes’ together, I was relieved. No one seemed to notice what we did.

Chapter Seven

A New Worry

When it looked like we couldn’t get through to southern Korea on the train, there was talk of going back north. Some, like the Manchurian Railroad people, tough Japanese engineers who lived in Manchuria for many years, thought that once the Soviets finished their rampage, the situation would be better up north than it was down here in northern Korea, surrounded by angry locals. Many of these people did go back but there were a few of us who still thought it would be better to somehow get through the 38th Parallel before they closed it down completely.

As it became clear we had to move somewhere, I cut up our blanket and made coats for Masahiro and Masahiko. The uncertain days passed into September. Our dan was ordered to leave the Agricultural School and move into an empty house on top of the hill outside town. We stuffed the bags of forty-nine people onto two ox-carts we borrowed from the school. We avoided the middle of town where we might run into Koreans eager for revenge, and instead walked around the village to the hill. But it was soon obvious that we wouldn’t be able to get the two ox-carts up the hill.

We collected our bags off the carts and carried them up. The house at the top had a small wooden sign, “Sensen samusho,” a reminder of its past life as a Japanese shinto shrine, one of many built by the occupying Japanese government. The shrine itself had been burnt down recently, perhaps by an angry mob celebrating the end of the Japanese occupation. But the residential building next door had miraculously escaped the fire. This house had Japanese tatami, rice straw mats laid inside. How nostalgic! There was nothing else inside. The thought of sleeping on comfortable tatami mats made us feel safer.

Beyond the remains of the shinto shrine, a mountain range rose into view.

In terms of size, the house contained an eight tatami mat size room, two six mat rooms, and two small four-and-a-half mat size rooms. Our group divided up into these five rooms. There was a kitchen and two toilets. Although the pump didn’t flow very well because we were at the top of a hill, if we left a bucket under the pump for the night, by morning there was a good amount of water in the bucket.

At night we saw the lights of the town below. Sometimes we even heard sounds from the town. But besides that, we had an interesting view. We saw below us everyday, open train cars going south overloaded with people. Mostly Koreans passengers, but we still wondered, “When can we go home to Japan?” As we obsessively wondered what to do, whenever we saw anyone on the trains who looked Japanese—we asked ourselves, “Has the hikiage repatriation started?”

After seeing some Japanese on the trains, my husband went to see if he could verify who and from where these Japanese might be. We felt better sleeping on tatami mats, outside of town and although we were a group of forty-nine strangers, it was refreshing to hear the sound of laughter from time to time.

We were fortunate to find a large number of futon quilts left behind by other Japanese who had already left. Many of these futon were wet and half rotted but when we dried them out, some of them could be restored back to decent shape. I took two of the quilts and used them for our bed. Around our house on the hill, wild white chrysanthemums blossomed with a few yellow ones scattered amongst them.

Our children regained their strength. Avoiding the main roads, the men went to town everyday to buy food. They bought back something that looked like hoshi-zakana dried fish and some hango, small metal pots for cooking. We cooked vegetables and fish. We bought and baked sweet potatoes, roasted corn and ate. My breasts swelled and I nursed Sakiko once again. We even talked about daily life, mundane things like, “Three ears of corn for one yen. That’s cheap…or that’s too expensive.” Using wood we picked up on the mountain, we cooked the food and felt good.

We were seventeen families, almost fifty people all together, in the five rooms. Living so close together, we had a new worry. Where to keep our money? We decided to hide our money tucked in empty cans—near the roots of trees, under rocks. Each family hid their money, not only from outsiders, but also from the other members of the dan. There had already been several thefts. My husband and I decided to divide our money into three parts, and to hide it outside and inside.

Everyone had to contribute to a pool of money to cover group expenses. It was frightening to think what would happen if someone inevitably ran out of money, and could no longer contribute their share. I wondered, “Would the rest of the dan look after the impoverished members?” I tried not to think of that. For now, we depended on the money from Manchuria. Later, we might go our separate ways but for now, we had to live together.

Once every ten days, we withdrew our Manchurian money and exchanged it for Korean bank certificates. One hundred yen became fifty yen. Japanese money was no longer accepted and we were running out of funds. The men went out to work everyday, doing anything to earn a little money. My husband got up early and come back late, exhausted after a full day of manual labor, but all I could offer him at the end of the day was one ear of corn or maybe an apple.