Where is My Husband Going?

In the yard there was a single small maple tree. This tree was in the shape of a sideways letter V and from the top, three branches sprouted from the same place. It was October when these maple leaves turned. We had to wear socks to bed, otherwise our cold feet woke us in the middle of the night, but the afternoons were still warm.

As I hung diapers to dry on the tree, I heard something. When I looked up, an airplane, one with markings that I had never seen before, flew north. A Korean man asked quietly, “Is Mr. Daichi here?”

I turned around to see the train station master standing there, half-smiling. Most of us didn’t know what was happening in the war but Mr. Daichi found a source. On his daily walks, he became friends with this Korean station master. I wasn’t surprised. Mr. Daichi was good with people—making anyone feel at ease. Every evening, he snuck down the hill and listened to the station master’s radio and heard all sorts of news. This is where we heard: the hikiage, the repatriation would begin in November.

I showed the station master up the hill to Mr. Daichi and, felt anxious—is there something new going on? By coincidence, I heard the same news about the November hikiage through my husband’s distant relatives, an elderly couple who lived nearby, called Old Man Gomi and his wife. He used to be an elementary school teacher in northern Korea. They lived in a small place and started quietly bringing us things (mostly old magazines, paper and other useful things).

Around October 20th, Old Man Gomi came around and told us he heard through another Japanese group that the hikiage would be in November. “If it’s possible, I wanted to ask if we could be included, to go home,” he said. My husband tried to find out where that rumor came from but Old Man Gomi didn’t know. Maybe it started with the station master’s information? Old Man Gomi laughed and went back down the hill.

Around October 25th, there was more activity in the town and more trains started coming and going. Our hearts beat with excitement—maybe we could go home to Japan! When the men returned that night, sounds of laughter filled with hope floated through every room. The next day, we started preparing candy and other portable food. But, other than trains passing through the station, three or more times a day, nothing happened.

A gentle knock on the front door woke us from a deep sleep on the morning of October 28th. It was Mr. Daichi’s friend, the station master again, but this time he asked for Dancho Oe and my husband to come outside together with Mr. Daichi. I felt uneasy. In every room, everyone woke up and we all quietly waited for the three men to return.

When they came back, I saw their faces were ashen, like those of the dead. I wondered, “What happened?” but our three men only said, “Hurry. Make breakfast,” and went into the small room to discuss something in private. When my husband came out to get a piece of paper, I asked him, “What’s going on?”

“I’ll make an announcement soon—just get things ready,” he said and rushed back to Dancho Oe and Mr. Daichi.

“Get ready for what?” I called out, but he didn’t answer me.

When I went outside, an early-morning fog completely covered the town. It was eerie to hear all sorts of sounds—children crying, things being moved—through the thick grey mist. Then from the school below us, I heard the shouting of men. All I could do was pace back and forth. “Get ready? How?” I thought, but I did as he asked and repacked all of our things.

Sounds of a horse climbing our hill were followed by the appearance of a man from the Hoantai Korean Police. He asked for our dancho to come right away. I couldn’t see where Dancho Oe and my husband went. Worried, I went out to wait. Out of the thick fog, my husband came back holding one of our ‘safes’, the tin can with emergency money. He hurriedly pulled out the money that was in the can.

“All Japanese men between the ages of eighteen and forty are to go to Heijo by train,” he said. “I’ve got some money for myself. I’m giving the rest to you.”

“What are you going to do at Heijo?” I asked.

“I don’t know. We might be sent to Siberia,” he said.

“Siberia?” I didn’t know what to say. The world was ending. Clutching the money wrapped in paper my husband gave me, I sank to the ground.

“Please hurry. Get my things ready. I don’t need money. Just the essentials,” he said nervously.

He had to get back to his duties for the group, taking care of the bookkeeping, and giving final instructions to those staying behind. Dancho Oe came back. “Within thirty minutes, all men between eighteen and forty years of age are to report to the front of the school below us,” he said. “Get ready right away.” A black cloud descended on everyone—except for Mrs. Nagasu whose face lit up when they announced “men up to the age of forty.” Her husband was forty-three. I hated the smirk on her face.

After they had their meeting, my husband came back. “This might be it. I may be leaving you for good,” he said as he put on the black suit I had repaired. We sat down to eat but couldn’t swallow the food. I stuffed the leftovers into a bento box for him. Looking through the clothes I packed in his rucksack, he said, “I don’t need this…or this,” and pulled out the winter clothes. I knew he was thinking of us. The Hoantai police came up to get our men.

“Hurry,” they said while avoiding our eyes.

When I tried to get him to take the blanket, my husband fought back fiercely. “I’ll manage,” he said. I pleaded with him, crying. Finally, I got him to take five hundred yen.

The final moment came and we looked at our baby, Sakiko still fast asleep on our blanket. Gently touching her cheek, he said, “She’s sleeping so well. She looks just like Masahiro when he was a baby.” Then he turned around and gazed at our eldest son who was standing beside me. Masahiro was doing his best to be brave. “This time, Daddy might not come back. Listen to Mommy, all right? All, right?” my husband said. Masahiro nodded and put his hand on my shoulder.

Masahiko was on my lap, his face nestled against my breast. He was only a two-year-old, still in need of mothering. At this tender age, he had been forced to deal with the arrival of his baby sister, and the war. Masahiko was so thin, his eyes seemed even bigger. He was my husband’s favorite and while I was busy with the other children, he took care of our middle child. One of their favorite activities was their walk to the bathroom every night. “Masahiko-chan, I want you to listen to Mommy, all right?” my husband said, but our son wouldn’t let go of my blouse. Instead, he stared at his father with huge terrible eyes.

My husband then turned to me. “Go home to Japan. Take care of the children.” There was so much to say but I couldn’t speak. As tears trickled down my face, I finally said, “Take care. All right?…Don’t get sick. All right?…Be sure to come back to us. All right?…”

Of our eleven men, those over forty years of age were: Mr. Narita, Mr. Daichi, Mr. Nagasu, and Dancho Oe. They would be allowed to stay with us. My husband and the six other men who were to be taken away from us gathered in front of our house. Facing us, one of them said, “Everyone…please be kind to each other. Take care of each other.”

After each man spoke, my husband came over one more time as I held Masahiko. He gently touched his son’s face. He used a favorite nickname and said, “Masa-chan, sayonara.” My little boy, who until now had been silent, suddenly started screaming. I wanted to scream even louder than him.

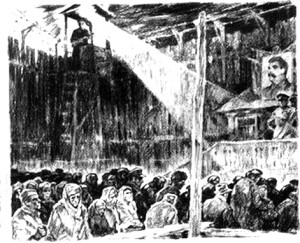

The fog began to lift. An open freight car was taking our men, and we stood on the hill to see them off. The train started moving slowly. Mr. Mizushima’s glasses glinted in the sun. I spotted my husband’s black suit right away. He waved his handkerchief and I waved a hand towel back. He waved his handkerchief in a circle. I waved my hand towel in a circle. We said good-bye. The train picked up speed and then passed behind a hill. October 28th was one of the saddest days of my life.