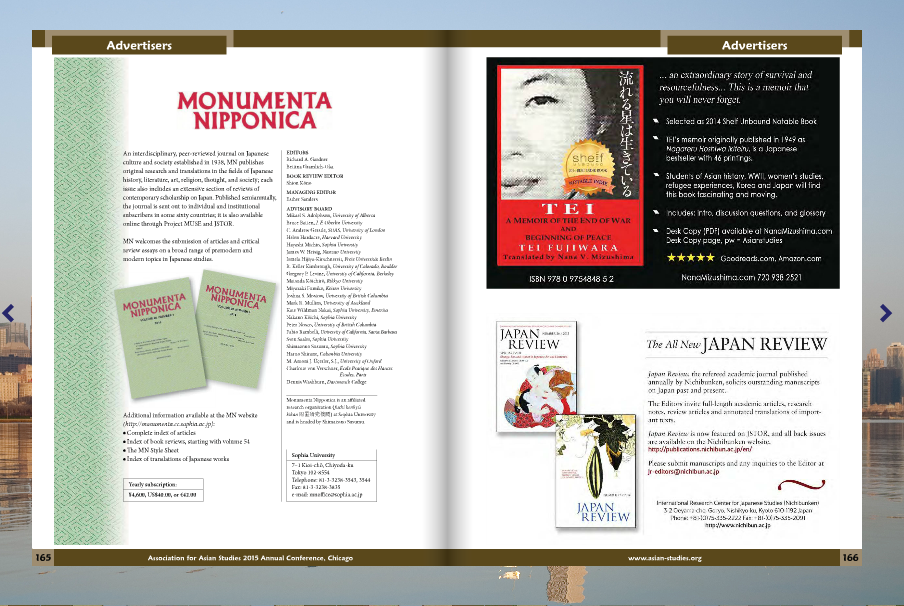

Almost seventy years ago, Tei Fujiwara wrote a memoir about her harrowing journey home with her three young children. But the story of her story is what every reader needs to know.

Tei’s memoir begins in August 1945 in Manchuria. At that time, Tei and her family fled from the invading Soviets who declared war on Japan a few days after the United States dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima. After reaching her home in Japan, Tei wrote what she thought would be a last testament to her young children, who wouldn’t remember their journey and who might be comforted by their mother’s words as they faced an unknown future in post-war Japan.

But several miracles took place after she wrote the memoir. Tei survived and her memoir, originally published in Showa Era 24 [1949] became a best seller titled Nagareru Hoshiwa Ikiteiru (Shooting Stars are Alive). Over the following decades, millions of Japanese became familiar with her story through forty-six print runs, the movie version, and a television drama. Empress Michiko, wife of the current emperor, urged her people to read Tei’s story.

Why should Westerners read this translation of her story? Tei wrote about men, women and children caught in the middle of the world’s most devastating war and how they coped. The suffering, endurance, and struggles she described reminded the defeated Japanese of their strength, their spirit, and hope in the future. Her sense of humor, compassion and love helped defuse anger and despair. She brought back a basic sense of trust towards former enemies, but also a honest new look at her own countrymen.

In many ways, Tei was a typical Japanese housewife, but she was also extraordinary. The memoir begins with a well-educated but sheltered young wife of a civilian scientist, who is a mother of three young children. Her keen insights in 1945-46—on the Koreans, fellow Japanese men, women and children, as well as the Russian soldiers and the American GIs—give us rare glimpses into a part of the world few Americans know.

Why did I translate Tei’s memoir? My initial reason for translating her book was personal. My parents both grew up and lived in Tokyo during the war. My father was 22 years old and my mother was 13 when the war finally ended after four long years. WW II devastated the lives of millions of Japanese civilians living in Japan as well as in Manchuria and other parts of Asia. Tei’s story resonates deeply with my parents’ generation.

Her memoir and family also influenced my family in unexpected ways. Tei’s younger son, Masahiko, became a mathematician, and came to the University of Colorado as a Visiting Scholar, where my father taught in the physics faculty. My parents enjoyed taking care of any visiting Japanese, and often invited them over to our house to stave off homesickness. I met Masahiko at one of the social gatherings at our home. I was 13 at the time but vividly remember meeting the young professor.

Over the next years, my family visited Tokyo several times. I heard first-hand, stories of how people survived and struggled after the war. The stories of the Fujiwara family as well as those of my own family encouraged me to study in Japan, obtain a

Masters degree in International Affairs from Columbia University, and work in international educational exchange over the next several years. This included several years as the Educational Information Officer at the offices of the Fulbright Program (Japan-U.S. Educational Commission) in Tokyo, and as the Japan Correspondent for The Chronicle of Higher Education newspaper.

The impact of Tei’s story on her own family life is also fascinating. After her memoir became a best-seller, Tei found herself in the public spotlight and dealing with the complexity of life after the war. At the end of this book, I included the afterwords she wrote in two of her later editions of her memoir.

Her husband, a former meteorologist, became an award-winning historical novelist himself, under the pen name, Jiro Nitta. Her children also wrote essays and books. In 2005, Tei’s son Masahiko Fujiwara wrote a book, The Dignity of a Nation, which has sold more than 2 million copies.

For Tei, this memoir was the achievement of a lifetime. She wrote it because she thought she might not live long enough to pass her story on to her children. In an interesting twist of fate, she has lived longer than most of us ever will. As of this writing, she is alive and well, ninety-six years old and living quietly in a senior home in Tokyo. Although Alzheimer’s has taken its toll and she no longer speaks or writes publicly, she still shares weekly meals with her three adult children, and her grandsons.

I feel fortunate to have had the privilege of translating her memoir while she is still alive. Her words are still as fresh as when she wrote them over sixty years ago. Tei’s story has also helped me in my own life as a mother of three children. By coincidence, I also have two boys and the youngest, a girl, about the same spacing in age as Tei’s three children.

When I first read her memoir, I was a full-time mother of three young children, adjusting to life in Colorado after living in Tokyo for two years, and in Jakarta for a year. Although I faced completely different challenges—divorce, financial hardship and starting over—her words encouraged me, inspired me, and gave me perspective.

My mother helped translate this memoir, by reading out loud passages from the book, and explaining what life was like in 1945 Japan. We spent many afternoons reading and discussing Tei’s stories, and we worked together to create the glossary in the back of this book. My mother and many of her Japanese friends say they have read and reread this book. When she introduced this book to me in the midst of all the turmoil in my life, I knew this was more than a casual book recommendation. The emotional impact of this memoir hasn’t diminished, even after sixty years. Often, during our afternoon talks—my mother would stop in the middle of a chapter she was reading to me—because she couldn’t continue. Her voice would break, quaver and die off to a whisper as her eyes filled with tears. Memories of the end of war and the beginning of peace are still very much alive.

Nanako V. Mizushima