The Day the War Ended

I woke up early and found myself lying on the cold floorboards of a cement building, on the edge of town where we arrived the night before. I lifted my head, so as not to wake the children, and tried to see where we were. Everyone was fast asleep—dressed as they were when we all collapsed upon arrival. The morning sun shone on the children and intensified their ghastly faces, white with fatigue beneath ugly streaks of coal dust.

Sensen Agricultural School took us in to join about three hundred Japanese refugees already here—mostly women and children. As the sleep slowly dissolved from my eyes, my first thought was, “I must wash Sakiko’s diapers.”

I slowly rose from beneath the single blanket that covered us, unwrapping my arms from around my three children, who remained asleep. I crept outside and after going up a little ways on a dew-covered farm road, I found a clear small stream and followed it up into the middle of the woods where a beautiful western-style red brick-building stood. When I went past the front of the building, a lovely view suddenly appeared.

It was a pretty town. More sturdy western-style buildings, perhaps a school or a library stood next to what looked like a church tower. Below that, several neat dwellings lined up, all of them still dark in the thin morning light. Mountains embraced this valley while a river ran through the middle of a town laid out in a square. A single lonely train track crossed the river, then wound around and disappeared into the mountains.

Behind our refuge, this school where we slept, the men were building a simple kitchen. They had set up a cook stove, a place to put the pots, and a communal serving area. Later that day they prepared a mixture of half soybeans with half white rice and made onigiri to distribute twice a day. But the soybeans must have gone bad. After eating, almost all the children got upset stomachs, and most of the adults ended up with a most unpleasant diarrhea.

A cow looked up at me in curiosity. Thank goodness, there was a cow at the agricultural school. Those of us nursing babies each received a small portion of her milk. We mothers were helped a great deal by this cow, but there were so many of us that the milk was not nearly enough. Those whose breasts stopped making milk became desperate as their babies became weaker and weaker.

Once we settled in, I dragged myself several times a day to the river to do the laundry. Sometimes I heard planes flying overhead and each time, I followed the contrails and wondered, “What will happen to us?”

On August 14th, around noon, a single plane began circling high in the sky. “There must be some good news,” we fervently hoped, and rushed outside to wave at the plane. As if to answer our signal, the plane scattered handbills. But they only contained a message from a senior officer of the Japanese Kanto Army asking, “Where are our families?” They only care about their own.

August 15th was a clear day. I was carrying Masahiko on my back, sitting under the poplar trees when—suddenly—bells started pealing. I could hear the footsteps of the agricultural school students as they gathered in their school yard. There must have been four or five hundred of them. A bald man we recognized as the headmaster stepped up to the speaker’s platform. I watched and waited for something to begin.

Then the headmaster waved his right arm at me, as if to tell me to go inside the school building. I looked around to see who he had waved at. There was no one behind me. He waved his hand again in big movements. I gave up on my day’s excursion and began slowly climbing up the hill back to our building.

Then suddenly, like a wave coming towards me, I heard strange sounds. I turned around and those sounds quickly became cries and moans. A male student with a white shirt and crewcut cried so sharply that icy shivers went up my spine. Without any further thought, I hurried back to our schoolroom. Something must have happened.

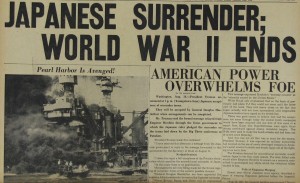

That was when I first heard the news. “The war is over,” announced Dancho Tono, his face pale and drained. As I watched his tears drop one by one to the ground, our nerves stretched to the breaking point. One woman burst into hysterical wails. Her cries sparked all of us. So many times, I wept since leaving Shinkyo. As I began to cry this time, I thought, “Where is my husband? Where is he hearing this news?”

Another fear quickly grew amongst us. “Would we all die now? What is going to happen to us?” Japan was defeated. Our world was coming to an end and something catastrophic would happen very soon. The evening of the fifteenth we prepared to flee as quickly as possible. Terrors of the worst kind filled our imagination. I sat with Sakiko strapped onto my back. If we had to run then I’d throw away everything I had in my pitiable rucksack. I took out the Longine watch my husband gave me and looked at it in the moonlight—it was past midnight. I had Masahiro and Masahiko go to sleep with their white cotton shoes on, ready to run at a moment’s notice. I watched their restless legs tangle together, then untangle as they slept.

The wait for morning was exhausting. I was stiff from sitting up for so long with the baby on my back. When dawn finally arrived, we were so frightened, our own shadows spooked us. But nothing happened. While the boys slept, I got up. Severe diarrhea sapped me of any strength I had left. But I continued, dragging myself up through a thick fog to wash the diapers.

Outside the school, crowds of Koreans passed by, they waved flags, and there was a festive mood flowing about the town. They were celebrating the end of Japanese rule. We felt nervous and uneasy for the rest of the day, especially when all the dancho ordered us to stay inside. The children and I huddled quietly in the classroom.

As the hours ticked by, we grew hungry. A few bold women from our group ventured out to climb the hill beyond out building where cornfields and apple orchards lay. They managed to get food from nearby people. But I was so afraid, too afraid to do as they did, so I watched them with envy as they came and went. I had money, but since I couldn’t go out, I tried to satisfy the children’s hunger by feeding them strings of lies.

When I separated from my husband, I had a three thousand yen certificate from the Bank of Manchuria and my post office savings book. But in this town, the Manchurian money was useless. I had managed to get to the post office once to get Korean bank certificates. Using them, I bought a few vegetables from the town market. But living in a group like this, there was little tolerance for individuals. When I approached our common cooking area to try to cook our own food, the men yelled at me and drove me off. I had no choice but to give up.

All four of us had diarrhea. Masahiro, my oldest, and I had it the worst. I knew we needed to eat okayu—rice gruel—but we didn’t have any. From the window I saw the Japanese Kanto Army families, their strong men, stripped to the waist, mixing big pots filled with okayu and good-smelling soup. The military families had a lot of supplies and we saw their storage containers filled with canned food, sugar, and various other items.

I envied them as they ate and enjoyed their food. It became obvious that those of us in the Meteorological Station dan were the poorest of the Japanese refugees here at the school. Why had our group not saved as many supplies? Why were we so poorly treated? I wondered. My husband was one of those who were treated as second-class citizens by the Japanese military authorities.

My life was soon reduced to walking a small triangle—from the corner of our room to the toilet, and then from the toilet to the small stream at the top of the hill where I washed the diapers, and then back to our corner. Back and forth. Back and forth. My diarrhea worsened. Then as Masahiro’s fever rose, he could no longer walk. I put him on my back and carried him along that triangle over and over.

In the toilet, I tried to check to see if there was blood in our stool, but the others waiting in line behind us complained for us to hurry, so I rushed out with Masahiro’s feverish, limp body in my arms. When we returned to our ‘home,’ I found Masahiko and Sakiko bawling, and the neighbors glared at me. Their eyes burned white-hot with hate as they wallowed in their own misery. I stopped talking to anyone the whole day. I scolded the children to be quiet and swallowed the bitter phlegm in my throat. As diarrhea tortured my body, walls of agony closed in on me, and the fever burned away everything in my mind. Everything except the desire to go home. The desire to go home and thoughts of my husband.