Shall We Go South?

I couldn’t rouse myself out of bed the next morning, maybe because I was too drunk with happiness—my husband was back. I didn’t want to get up. I wanted to let him take care of me again—to amaeru—that delicious feeling of losing myself in him. I was so happy that I could relax, even a little. But two days after he arrived, there was a change in our group. Dancho Tono learned his missing wife was in Chinnanbo, a town further south, and he decided to leave our group to go find her.

Who is going to be our next dancho? This was wartime and we couldn’t depend on the usual procedures we followed for this sort of thing. They would probably select someone based on a his former job. Out of the eleven men, the ones most likely to be chosen were Mr. Narita and my husband In addition to these two, there was Mr. Oe who was ten years older and used to be a manager. So there were three candidates. Watching the eleven men seated in a circle in the middle of the room, intently talking, it looked like the dancho job was going to be handed to my husband, but I prayed that he would turn the job down.

Mr. Narita was a weak, scholarly man and I dismissed him, thinking, “He’s not much use in this situation.” Next they talked about my husband. I was worried sick that he would end up with the job because I knew my children and I would end up secondary to any dancho responsibilities. They kept talking through the morning but still hadn’t made a decision yet. When my husband came back to talk with me during their break, I told him to not accept this job, “Never!” He didn’t say anything but just nodded.

In the afternoon, it was decided. The new dancho would be Mr. Oe, who was older and known for being a tough boss. Next in line—fuku dancho, the assistant head, would be my husband. I was uneasy but grateful that he wasn’t picked to be the dancho. Dancho Oe and fuku-dancho my husband, they were announced to the other Japanese.

Everyday at one p.m. representatives from all the refugee dan met at an elementary school in the center of town. When Dancho Oe and my husband, the fuku-dancho, got back from these meetings, we gathered round to hear the latest news. But who knew if the information was really reliable or not. I thought a lot of it was gossip, or just more propaganda from the government. I waited anxiously for my husband to get back because he sometimes managed to pick up some apples or Korean rice cakes on the way back.

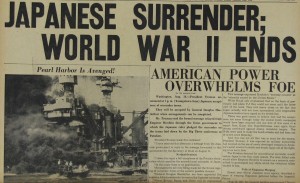

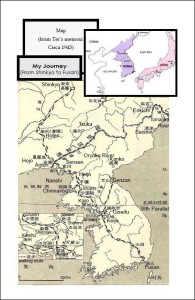

The information from these meetings made everyone uneasy. There was always talk of something terrible about to happen to the Japanese—the hated former colonizers of Korea. More and more Japanese fled south when the trains began to run as they did before. I thought we should take the chance, too, and go to Jinsen in southern Korea, rather than stay here northern Korea with people I didn’t know. The former head of the meteorological station, Mr. Wadachi, his wife and others would be down south.

I had the feeling that if we could somehow get to Jinsen, we could escape this terrible situation. “Now. Now, we should go south,” I urged my husband. When he was extremely worried, a deep wrinkle would appear between his thick eyebrows. He said, “But what about the other families who get left behind?”

“But in this situation, we don’t have the luxury of thinking about other families,” I said.

“That’s just your selfish logic,” he shot back. “It’s true that if we go south, we would be saved. At Jinsen, there’s not just Mr. Wadachi, there are a lot of people I know from the Korean meteorological station. That’s true that we would be better off than we are now. But, who’s going to help these other families get home?”

“What are you saying? There’s a great dancho here, and there are a lot of other men who could do the job,” I said.

“You don’t understand,” he said. My husband became very serious.

Did he intend to endanger the lives of all five members of our family and have us stay in this dangerous place? All because of his sense of responsibility, his devotion to other Japanese refugees, and his willingness to meddle in their problems?

I said, “Times have changed. The meteorological station is gone. And you are not a manager of anything now. You have no department. If there’s any connection, it’s just the people who were civil servants, and they look to you as a mentor. Why should your freedom be held hostage by forty-nine strangers? How is that a reason for staying behind?”

I ignored Mr. and Mrs. Mizushima who sat next us. Mr. Mizushima wiped his glasses, but he was obviously listening in on our fight. I pressed my husband even harder. But he dug in his heels, and ignored my pleas. “My boss, Mr. Taya, asked me to look after these people. If I go now, this dan will become a mess,” he said.

My husband’s idiocy, as he went on and on about his duty and his obligations finally got to me. I shouted, “You’re just thinking about yourself. You have a twisted, one-sided prejudice against your own family. Stupid ideas about your own superior character and sense of justice are all you care about!”

“What? Superior character?” he angrily sputtered.

I shot back, “That’s right. I don’t know what Mr. Taya said to you but you’ve gotten so full of yourself, you think you are the only honorable person here. I’m sick of your thinking. Do whatever the hell you want,” and I turned away from him.

Out of the corner of my eye, I saw Mrs. Mizushima cover her mouth. She trembled and clung to her husband as I spit out my words. My husband didn’t try to argue. He finished his dinner quickly and gazed at the group as everyone got ready for bed. His eyes focused on two or three families in particular, those with children. The Mizushima’s leaned their heads close together, to gossip about our fight, no doubt. From time to time, they glanced back at us. My husband finally noticed them.

“I’ll think about it tonight,” he said.

After that he didn’t say a single word.

When he ended his silence the next day, he began talking with Dancho Oe about going south. They decided that those who wanted to go south should be allowed to do so. He said, “Let’s ask everyone what they want to do.” At the next group meeting, the idea of going south was brought up. Many were pessimistic. They said, “The more we move, the more dangerous it will be. If we just stay where we are for another month, we can go back to Japan with those from the north.” There were many who believed this nonsense.

We devoted the day to deciding what the dan should do but the discussions just went around in circles, with no end in sight when we went to sleep that night. The next day, the dan still couldn’t reach an agreement and I grew irritated with all the waffling. The morning of the third day, my husband made an announcement to everyone. “Not as your fuku-dancho, but as an individual and a family man, I’ve decided to go south. If anyone else wants to come with us—we leave tonight.” After saying that, we began preparations to leave. Then the people who were so opposed to him suddenly changed their minds and began preparations themselves. Soon everyone joined in the preparations.

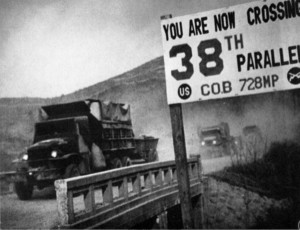

Mr. Kimoto and another man ran to the train station to check on the departure times. One man told us a train would leave at 6 p.m. that day. But as we hurriedly packed, Mr. Kimoto came running back from the train station and said, “Mr. Fujiwara, it’s no good. Starting today, the trains are not allowed further than Heijyo, in northern Korea, which is only a little ways south of us.”

I felt that whatever we decided to do was going to determine our fates. (I think this was August twenty-fourth.) They said the 38th Parallel was closed and trains would no longer be allowed through. We stopped packing and were stunned into silence. My husband remained quiet and gazed out toward the eastern sky for a long time.